- About

- Visit

- Exhibitions

- Collection

- Overview

- Search the Collection

- Recent Acquisitions

- SPOTLIGHT ON …

- Bouguereau’s “Amiable” Pictures Cross the Atlantic

- Back to Work

- The Allure of Animals in Academic Art

- Classical Mythology in 19th-century French Art

- Celebrities: Portrait medals in 19th-Century France

- Oriental “Native Types” from the Dahesh Collection

- Recording Islamic Architecture and Design

- French Natural Selections

- Painting Piety from the Dahesh Collection

- About Face: Learning to Draw Emotion through Expressive Heads

- From St. Petersburg to Paris: The Education of Russian Artists in France

- Picturing the News: The Birth of the Illustrated Press

- Egyptomania: 19th Century Depictions of Ancient Egypt

- The Franco-Prussian War and Its Aftermath in French Art

- Painting Pompeii: From Neoclassicism to the Néo-Grecs

- The Spanish Orient and Henri Regnault (French, 1843–1871)

- Women Artists Who Dared II: Jeanne Thil (French, 1887–1968) and Marie Hadad (Lebanese, 1889–1973)

- Women Artists Who Dared I: Rosa Bonheur (French, 1822–1899) and Elizabeth Gardner Bouguereau (American, 1837–1922)

- Peder Mork Mønsted’s (Danish, 1859–1941) Poetic Views of Nature

- Publications

- Programs

- Shop

- News

Search Results for: ‘alma-tadema’

-

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Study for Joseph, Overseer of Pharaoh’s Granaries

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (Dutch/British, 1836–1912)

Study for Joseph, Overseer of Pharaoh’s Granaries, ca. 1874

Pencil and watercolor heightened with gouache on card, 16 3/4 x 22 in.

2014.7

This sheet by Alma-Tadema is related to the splendid painting in the Dahesh Museum collection, Joseph, Overseer of Pharaoh’s Granaries (acquired in 2002), first exhibited in 1874 at the Royal Academy. The subject derives from the Book of Genesis, with Joseph seated on a throne in his role as the Pharaoh’s overseer of the royal granaries, accompanied by a scribe reading him the account of sales. The finished painting follows the general composition and colors of the sketch, with the addition of details of the ancient Egyptian decorations and accoutrements. This study was in the collection of Andy Warhol.

-

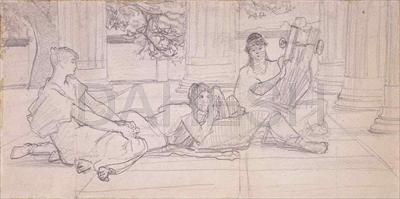

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, First concept for A Reading of Homer

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (Dutch/British, 1836–1912)

First concept for A Reading of Homer, ca. 1882

Pencil on wove paper, 4 1/2 x 9 in.

1997.2

This is a preparatory study for A Reading of Homer (1885, Philadelphia Museum of Art), one of the artist’s key pictures. An inscription on the reverse of this drawing written by the dealer Charles Deschamps (and dated 1902) reads: “One of the ideas L. Alma Tadema had for a picture A Reading of Homer to be submitted to Mr. H[enr]y Marquand of New York, who subsequently commissioned Tadema to paint him a picture of the subject, but of which the composition was quite different.”

Deschamps was the nephew of the famous London dealer Ernest Gambart, an extremely influential figure in the development of the 19th-century art market. Even though Alma-Tadema ultimately painted a very different painting for Marquand, he did not completely discard the idea he had jotted down on this drawing, as he repeated the exact composition of the two girls on the left in a later picture called Love’s Votaries (1891, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle-upon-Tyne).

-

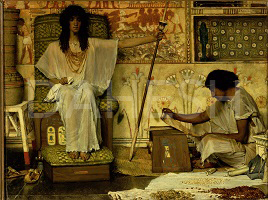

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Joseph, Overseer of Pharaoh’s Granaries

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (Dutch/British, 1836–1912)

Joseph, Overseer of Pharaoh’s Granaries, 1874

Oil on panel, 13 3/4 x 18 in.

Signed and inscribed upper right: L. Alma-Tadema op CXXIV

2002.38

Although Alma-Tadema specialized in scenes from ancient Greece and Rome, he also painted several scenes set in ancient Egypt—including the present work, which was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1874. Drawn from the Old Testament’s Book of Genesis, it depicts Joseph seated on a throne in his role as the Pharaoh’s overseer of the royal granaries, while a scribe works on the floor next to him, carefully counting each piece of grain.

Alma-Tadema based the ancient Egyptian decorations and accoutrements in his picture on actual artifacts. He owned a large collection of photographs of archeological sites and objects, and one showed a photograph of a distinctive wig found in a tomb at Thebes. Alma-Tadema patterned Joseph’s wig after the photograph, although the wig was believed to have been worn by a woman, not a man. The wall painting behind the figures is from the tomb of Nebamun in the British Museum and the cartouche on the throne is that of Tuthmosis II, who ruled during the Eighteenth Dynasty (ca. 1504–1450 BC), the period 19th-century scholars believed to have coincided with Biblical Egypt.

-

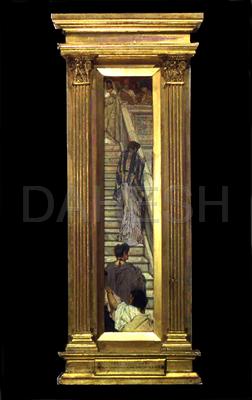

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, The Staircase

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (Dutch/British, 1836–1912)

The Staircase, 1870

Oil on panel, 16 3/4 x 3 3/4 in.

Signed upper right: Alma Tadema

2000.18

The Staircase was submitted by the artist as a lottery prize to a London exhibition for the benefit of the “Distressed French Peasantry” in districts occupied by the German army during the Franco-Prussian war (1870–71). Alma-Tadema posed himself a formidable challenge in dealing with such an unusually-shaped panel, but his decision to paint four women in Roman dress ascending a marble staircase resulted in a striking image. The painting is in its original frame, which to an extent forms part of the composition— the two classical columns expand upon the implied architectural space and compensate for the narrow width of the panel. Together, the starkly elongated format, the figures seen from the back, and the generic title all construct an enigmatic image that has true cinematographic qualities. Likewise, the manner in which several figures are cut off in the composition, as well as their graceful poses, suggest knowledge of Japanese art, which was extremely popular in Europe at the time, mainly in the form of prints.

-

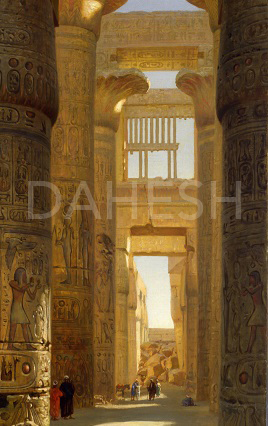

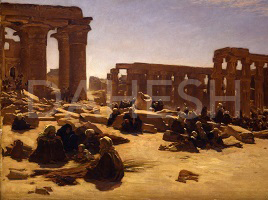

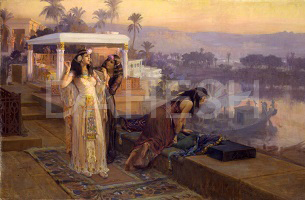

Egyptomania: 19th Century Depictions of Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt was a continual source of inspiration for 19th century artists, who documented its ruins, depicted historic events, and reimagined everyday life from the Nile’s distant past. Europe’s fascination with Egypt was ignited by Napoleon Bonaparte’s expedition in 1789, which resulted in the discovery of the Rosetta Stone (196 BC, British Museum) and the publication of the encyclopedic Description de l’Égypte (1809–1828), compiled by Napoleon’s team of scholars. Containing more than 800 engravings, works like Charles-Louis Balzac’s view of the ruins on Philae or André Dutertre’s interior of the tomb of King Ramsses II inspired Europe’s Egyptomania, a taste for ancient Egyptian art and culture.

Travel to Egypt was both costly and time consuming––especially at the beginning of the 19th century––but artists could learn about the Nile’s history from books and new archaeological collections in Europe’s museums. These institutions had been greatly enriched by tomb raiders and excavators like Bernardino Drovetti, Henry Salt, and Giovanni Belzoni, who assembled Egyptian collections for the Louvre, the Turin Museum, and the British Museum. Lawrence Alma-Tadema, a leading painter of antiquity, drew on several pieces from the British Museum in his work Joseph, Overseer of Pharaoh’s Granaries (1874), including a wall painting from the tomb of Nebamun and a cartouche of Tuthmosis II, seen on Joseph’s throne. Artists also found inspiration in illustrated books––Edwin Longsden Long, for instance, included in his painting Love’s Labour Lost (1885) a wall mural, toys, vase stand, and stools, illustrated in Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians (1837), by John Gardner Wilkinson.

As travel to Egypt became more accessible, paintings of ruins and ancient sites became increasingly popular. In The Temple of Karnak. The Great Hypostyle Hall (1890), Ernst Karl Eugen Koerner emphasizes the hall’s enormous scale, while Joseph Farquharson’s The Ruins of the Temple at Luxor (ca. 1890) focuses on the general impression of another famous site, though he includes distinctive details like the papyrus bundle columns to the right of the temple. Hermann Corrodi, who first travelled to Egypt during the winter of 1876–1877, used the Kiosk of Trajan on Philae as a backdrop for his genre scene of native men by a fire.

Egyptomania was equally strong in America, and architects produced Pharaonic buildings such as the Washington Monument (Washington D.C.), while painters like Frederick Arthur Bridgman created dreamy works like Cleopatra on the Terraces of Philae (1896). One of several imaginary scenes that Bridgman set in ancient Egypt, the work was acquired by William Randolph Hearst, who hung it at his California castle, San Simeon. The fascination with ancient Egypt continued in both America and Europe into the Art Deco period, thanks to Howard Carter’s discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922.

-

The Franco-Prussian War and Its Aftermath in French Art

The turmoil of 1870–1871—the Franco-Prussian War, the Siege of Paris, and the Commune—upended the lives of many French artists. Artistic circles like the Café Guérbois group were split apart, as Cézanne fled to L’Estaque, Bazille fought and died, and Monet, too old to serve, waited out the conflict in London alongside Charles Daubigny and Jean-Léon Gérôme. Others were brought closer together, such as Georges Clairin and Henri Regnault who hastily returned from North Africa to enlist, though Regnault was later killed at the Battle of Buzenval. Rosa Bonheur, unable to serve because she was a woman, joined a local militia and even went out one night to fire on a Prussian camp. Several notable artists, including Tissot, fled to London after the war because of their involvement in the Commune. The crises in France even touched foreign artists—Lawrence Alma-Tadema donated The Staircase (1870) as a lottery item to a London exhibition benefiting the “Distressed French Peasantry” in German occupied regions.

The events of what Victor Hugo called the “année terrible” (terrible year) left an indelible mark on the French psyche that is evident in many works of art. Gustave Doré painted three massive works that confronted these horrors; The Enigma (1871, Musée D’Orsay), The Defense of Paris (ca. 1871, Francis Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College), and The Black Eagle of Prussia (1871). The topic was deeply personal for Doré who was a native of Strasbourg, a city routed by the Germans early in the conflict, an event which encouraged him to join the National Guard. Ernest Meissonier, who also served in the war—as a superior officer to Manet—painted his own allegory of France’s crushing defeat and Paris’ tragic fall in The Siege of Paris, 1870–1871 (ca. 1884, Museé D’Orsay).

Early public monuments to the war mourned the dead and paid respect to the resilience of those who fought. One of the best known works on this theme was Marius Jean Antonin Mercié’s Gloria Victis (The Glory of the Victim, ca. 1874), which shows an allegorical female figure resembling Nike of Samothrace (ca. 200–190 BC, Louvre), as she carries a vanquished French soldier. By the end of the 1870s Paris had recovered, and the Third Republic began commissioning monuments that glorified both the war and the new government. In 1879 the Prefecture of the Seine, for instance, held a competition for a new monument on the theme of Defense, to be constructed in Courbeville, a site where the French had fought the Prussians. Numerous artists submitted entries, including Auguste Rodin, but the commission went to Louis-Ernest Barrias. His work, The Defense of Paris (1879–80, Rondepoint de la Défense, Paris), acknowledged that though France lost the war, they had fought valiantly and would continue to face their enemies undaunted.

-

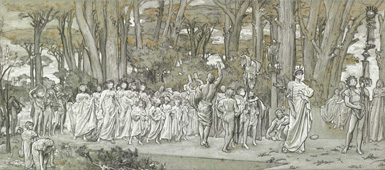

The Essential Line: Drawings from the Dahesh Museum of Art

Frederic, Lord Leighton, P.R.A. (British, 1830–1896), Study for Daphnephoria, before 1876, charcoal and pencil heightened with white wash on blue paper, 8 x 17 3/4 in., 2012.10.

Although drawing was an important training practice in Renaissance Italy, it was the Paris École des Beaux-Arts in the 19th century, the most influential art school in the Western world that instilled in artists the benefits of observation and constant drawing as the foundation for art making. The Essential Line features 40 drawings from the Dahesh Museum of Art by well-known artist like Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Rosa Bonheur, Léon-Joseph-Florentin Bonnat, Gustave Doré, Theodule-Augustin Ribot, Léopold Robert, as well as other equally gifted contemporaries. Arranged in 5 thematic sections, the exhibition explores the importance of drawing during the 19th century, whether as an educational tool, studies for paintings or sculptures, rapid sketches produced en plein-air (onsite) for future reference, or finished works of art.

The exhibition is accompanied by a full-color publication, The Art of Drawing: Selections from the Dahesh Museum of Art.

-

DAHESH MUSEUM OF ART ANNOUNCES FIVE NEW ACQUISITIONS

— World-Renowned Collection of 19th-Century Art Continues to Grow

Prior to Moving to New Museum Space —

New York, April 1, 2015 – The Dahesh Museum of Art today announced the acquisition of five new works that will significantly enhance its world-renowned collection of 19th-century art. The acquisitions, spanning 1851 to 1874, include three bronze statues, one oil on canvas painting, and one pencil and watercolor study heightened with gouache on card. The works are by artists Marius Jean Antonin Mercié (1845–1916), Aimé-Jules Dalou (1838–1902), Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899), and Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836–1912).Rosa Bonheur was the focus of an international retrospective created by the Dahesh Museum of Art in 1997; this is the seventh work by Bonheur to enter the Dahesh Museum collection. The watercolor study by Alma-Tadema is the preparatory work for a finished painting that is also within the Museum’s holdings. Alma-Tadema is among the most collectible Victorian artists (his painting The Finding of Moses sold at Sotheby’s in 2010 for $36 million). The three sculptures, by artists Mercié and Dalou, were a gift from Tracy and Laurel Pulvers.

“We are grateful to add these important works to our collection, and to eventually make them available to the public once we open at our new space at 178 East 64th Street,” said J. David Farmer, Director of Exhibitions for the Dahesh Museum of Art. “We have been actively acquiring new work for the past four years, and these works expand our growing insight into the 19th century and elaborate upon works we already possess.”

New Acquisitions

Marius Jean Antonin Mercié (French, 1845–1916)

David, ca. 1872

Bronze, brown patina, 25 1/2 x 12 3/4 x 17 7/8 in.

Signed on base, top right: A. MERCIÉ. Stamped on base at side back center: REDUCTION MECANIQUE A. COLLAS BREVETÉ.

Gift of Tracy and Laurel Pulvers

2014.4Mercié, one of the most successful sculptors of late 19th- and early 20th-century France, began as a pupil of François Jouffroy and Alexandre Falguière at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He won the Prix de Rome in 1868 and found immediate success with the first plaster model of David that he executed while in Rome. This sculpture offered a glimmer of hope for France after its crushing defeat by Prussia in 1871. David, armed with a slingshot, brought down the giant Goliath, proving that France too could triumph over its enemy. The State awarded Mercié the Legion of Honor and in 1872 commissioned a bronze version of David (Musée d’Orsay). The Barbedienne foundry cast a miniature version in six different sizes.

Marius Jean Antonin Mercié (French, 1845–1916)

Gloria Victis (Glory of the Vanquished), modeled ca. 1874, cast after 1879

Bronze, dark brown patina with gilt highlights, 36 5/8 x 21 x 16 in.

Signed on base right: A. MERCIE. Inscribed on base at front edge: GLORIA VICTIS. Foundry mark on back base: F. BARBEDIENNE, Fondeur Paris. Stamped on back base: REDUCTION MECANIQUE A. COLLAS BREVETE.

Gift of Tracy and Laurel Pulvers

2014.3Mercié executed the plaster model for this group while studying in Italy as a Prix de Rome boursier and exhibited it at the 1874 Salon. The winged female figure carrying a wounded soldier holding a broken sword expresses the loss and sacrifice of the French at the hands of the Prussians in the 1870-71 war. The sculpture won critical and popular acclaim. In his review of the Salon that year, the critic Jules-Antoine Castagnary observed: “while monarchists quarrel over the debris of our battered fortunes…there exists a young sculptor who has undertaken to speak directly to our nation and to console our people who have suffered so much.” Mercié received a medal of honor, the city of Paris purchased the sculpture for 12,000 francs, and the model was cast in bronze by Thiébaut et fils (Musée du Petit Palais, Paris). Replicas of it adorned monuments dedicated to those who served in the Franco-Prussian War in many towns and cities throughout France, and the Barbedienne Foundry provided bronze reproductions in different sizes.

Aimé-Jules Dalou (French, 1838–1902)

The Woman of Boulogne

Bronze, green patina, 24 3/4 x 7 7/8 x 6 5/8 in.

Signed on base back top: Dalou. Foundry mark on base back bottom edge center: SUSSE Fres PARIS …rcue. Foundry mark on base bottom right: SUSSE FRÈRES EDITEURS PARIS. Inscribed on base bottom right: Susse Fes EJes Paris

Inscribed on base, bottom right: Susse Fes EJes Paris

Gift of Tracy and Laurel Pulvers

2014.5Best known for his public monuments in Paris, in 1870 Dalou began to create statuettes of women. During his exile in London from 1871 to 1879 following the fall of the Paris Commune, he executed a series of women from Boulogne—a theme made popular by the paintings of Alphonse Legros, who also lived in England at that time. The original composition, entitled Palm Sunday at Boulogne, was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1872 and purchased by George Howard, later Earl of Carlisle. A girl returning from church clasps a prayer book and a branch of leaves, referencing the Palm Sunday mass. In London, Dalou frequently exhibited at the Royal Academy and taught at the National Art Training School in South Kensington (later the Royal College of Art), where he had a profound influence on the development of British sculpture

Rosa Bonheur (French, 1822–1899)

Going To Market, 1851

Oil on canvas, 19 x 27 1/4 in.

Signed and dated lower right: Rosa Bonheur 1851

2014.6When 29-year-old Bonheur painted Going to Market, her reputation as an animal painter was already firmly established. The composition, peasants with their ox-drawn carts, demonstrates Bonheur’s command of animal anatomy, which she had studied at horse fairs, cattle markets, and in the family menagerie. While Bonheur won the highest artistic and governmental honors in France, her works were also greatly admired in Great Britain and the United States.

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (Dutch/British, 1836–1912)

Study for Joseph, Overseer of Pharaoh’s Granaries, ca. 1874

Pencil and watercolor heightened with gouache on card, 16 3/4 x 22 in.

2014.7This sheet by Alma-Tadema is related to the splendid painting in the Dahesh Museum collection, Joseph Overseer of Pharaoh’s Granaries (acquired in 2002), first exhibited in 1874 at the Royal Academy. The subject derives from the Book of Genesis, with Joseph seated on a throne in his role as the Pharaoh’s overseer of the royal granaries, accompanied by a scribe reading him the account of sales. The finished painting follows the general composition and colors of the sketch, with the addition of details of the ancient Egyptian decorations and accoutrements. This study was previously in the collection of Andy Warhol.

About the Dahesh Museum of Art

The Dahesh Museum of Art is the only institution in the United States devoted to collecting, exhibiting, and interpreting works by Europe and America’s academically trained artists of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Dahesh serves a diverse audience by placing these artists in the broader context of 19th-century visual culture, and by offering a fresh appraisal of the role academies played in reinvigorating the classical ideals of beauty, humanism, and skill. Visit us at: http://www.daheshmuseum.org.

-

Rediscovering Egypt

Rediscovering Egypt:

The Collection of the Dahesh Museum of Art

The 2006 Dahesh Museum’s exhibition Napoleon on the Nile explored the legacy of Napoleon Bonaparte’s brief occupation of Egypt and how the interaction between military power and scientific knowledge shaped the West’s enduring image of that country. Rediscovering Egypt: the Collection of the Dahesh Museum of Art, on view in Naples, Florida, at the Baker Museum of Art, January 25, 2014 — May 18, 2014, co-curated by Director of Exhibitions David Farmer and Associate Curator Alia Nour, broadens the scope of the earlier exhibition by surveying the West’s fascination with Egypt and its diverse visual representations from 1798 until 1890. With over 90 works from the Dahesh Museum of Art, the Mervat Zahid Cultural Foundation, and a private collection, the exhibition features superb illustrated engravings from the monumental publication Description de l’Égypte and magnificent 19th-century Orientalist paintings by European and American artists such as Charles-Théodore Frère, Edwin Long, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, and Frederick Bridgman. Splendid prints after David Roberts and Jean-Leon Gérôme, together with lavishly illustrated books such as Émile Prisse d’Avennes’ magisterial L’Art Arabe, document a century of intense interest in the Orient (as the region was termed in the 19th century). With its broad themes and rich imagery, this exhibition demonstrates that the West’s visions of Egypt were fostered by many factors — not only political interest, but also new scientific and technological advances, methods of transportation, and communications, as well as Romanticism, and changing art market. The Dahesh Museum of Art is one of the few institutions anywhere that could mount such an exhibition with its own resources and connections.

-

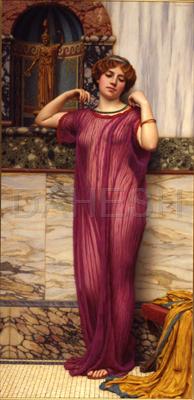

John William Godward, The Necklace

John William Godward R. B. A., British, 1861–1922

The Necklace, 1914

Oil on canvas, 19 3/4 x 13 1/2 in.

Signed and dated upper right: John Godward 1914

1997.66

Godward’s artistic development coincided with the final flicker of Victorian classicism, a tradition that celebrated beautiful, untroubled women in a luxurious ancient world. He enjoyed a highly successful career exhibiting regularly at the Royal Academy between 1887 and 1905, but an increasingly hostile art world open to modernism, coupled with his own depression, led him to commit suicide at the age of sixty-one.

Although he is usually considered a follower of better known painters such as Frederick Lord Leighton and Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Godward differed in his vision of antiquity. He rarely drew from history and mythology like Leighton, and did not produce the archeological reconstructions of Alma- Tadema. Instead, Godward specialized in portraying lovely, gracefully languorous women — usually dark-haired with see- through gowns — often alone in settings that evoke an opulent but unspecified Greco-Roman environment. There is little activity and even less narrative in this idyllic realm. His astonishing ability to portray variegated marble and intricate drapery folds is apparent in The Necklace. Here, the physical charms of a young woman are all but revealed by the diaphanous fabric of her garment, in stark contrast to the folds adorning the bronze statuette of Athena, the virgin goddess of wisdom, which appears behind in a mosaic-decorated niche.