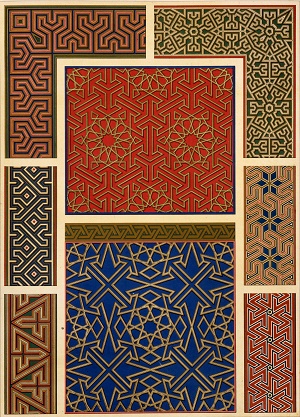

Spiégel, after Achille-Constant-Théodore-Émile Prisse d’Avennes (French, 1807–1879)

Arabesque: Assembled Wooden Compartments and Borders

From L’Art arabe d’après les monuments du Kaire depuis le VIIe siècle jusqu’à la fin du XVIIIe par Prisse d’Avennes. 3 vols. Paris, Ve A. Morel et Cie, 1877, vol. 2, pl. 94

Color lithograph, 19 1⁄4 x 13 3⁄4 in.

Printed lower left: Lith. par Spiegel / Vve A.MOREL & Cie, Libraires; lower center: Prisse d’Avennes; and lower right: Imp. Par Lemercier & Cie / Ordre de publication No

1999.10

The engineer, artist, and writer Émile Prisse d’Avennes was also a renowned Egyptologist of the 19th century. Like many French Orientalists, he eagerly explored the region, traveling to Greece, India, and Palestine before settling in Egypt and worked from 1827 as an engineer and professor of topography. Prisse grew fascinated by both Pharaonic and Islamic monuments, and in 1836 he resigned his post to study Egyptology and Islamic culture. Dressed in local clothing, speaking fluent Arabic, and using the name “Idris-Effendi,” he traveled throughout Egypt and elsewhere in the Middle East for 17 years. After a second sojourn in Egypt in 1858, he returned to France with hundreds of notes, folio drawings, photographs, sketches, tracings, and rubbings, all documenting buildings and decorations, some of which have since disappeared. Prisse published several books, including his colossal three-volume L’Art arabe, an extraordinary survey of Islamic architecture, decoration, and applied arts.

Published between 1869 and 1877, L’Art arabe includes 200 large color and engraved plates, of which 137 are color lithographs—mostly after Prisse’s on-the-spot drawings. Prisse greatly admired the Islamic style, especially that of Egypt and Syria, and suggested that its superiority could save Europe from what he considered its current aesthetic banality. Like some of his other plates, Arabesque: Assembled Wooden Compartments and Borders is essentially a decorative invention with various architectural fragments showing the viewer how patterns could be used engagingly in different colors. To achieve his extraordinary opaque effects in these plates, Prisse employed the advanced printmaking technique of color lithography—a decision encouraged in large part by Owen Jones’s sumptuous two-volume publication on the Ahambra (1842–45).