![Fig. 6. (Phot. Bert)., 'La Samaritaine (premier acte). La Samaritaine, Sarah Bernhardt. Jésus, M. Brémont.' Illustration for L[éon] Brémont, “'Musique: Festival Pierné, Conférence de M. L. Brémont,'” 'Journal de l’Université des Annales,' 5e année (année scolaire, 1910–1911), 1, no. 4, (1 Février 1911): 231, Dahesh Museum of Art. Fig. 6](http://www.daheshmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Fig-6-452x300.jpg )

In sum, feet may be taken by the holy Church as symbolizing the poor and humble. … the poor may be called the feet of the Church, and to caress the feet is to caress the poor of Christ *

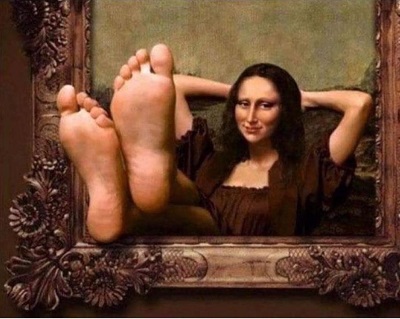

With the Louvre reopening, Mona Lisa is putting her feet back down on the ground (fig. 1). Ironically, the dusty state of the lady’s feet here is more in keeping with Caravaggio than Leonardo.

Influenced by the Counter Reformation, Caravaggio’s art brought worshippers physically, and therefore mystically, into closer contact with the church. His early Baroque art was deeply sensuous—Caravaggio’s Madonna of Loreto (fig. 2, ca. 1605–06, Cavalletti Chapel, Church of S. Agostino, Rome) gave (real) pilgrims to Rome direct contact with the Virgin and Child via the feet of the humble (and almost tangible) pilgrims depicted parallel to the picture plane.

Caravaggio’s star fell during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as Academic art looked to the High Renaissance and its refined Classicism for its imagery, which privileged idea over feeling. In The Water Girl (fig. 3, 1885), William-Adolphe Bouguereau emulated Greek and Roman sculpture, Raphael, and Ingres, in the guise of a modern French peasant. While the model Bouguereau painted was from his native village, the parallel ended there—the smooth sheen of this image, without a speck of visible dust, particularly on the exposed feet, had nothing to do with humble toil.

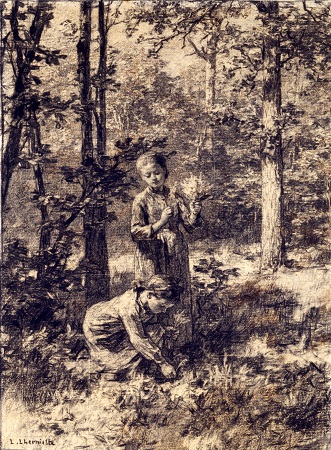

Leon Lhermitte’s Picking Lilies of the Valley (fig. 4, 1887), a charcoal illustration done for pastoral poet and novelist André Theuriet’s La Vie Rustique (1888, text, p. 223; illustration, p. 225), also depicts contemporary peasants as icons of serenity and stability. The artist leaves it to the author to note that the pickers’ hands and feet, scraped by the brambles, are covered in blood as a result of their toil. This reinforces the peasants’ sacred relationship to the lilies, traditional symbols of purity and sacrifice identified with the Virgin. Sadly, this holy effort goes unrecognized in the city, where the flowers are sold to “the bourgeoisie, poets and lovers [who] voluptuously inhale the smell.”

By the end of the nineteenth century the Catholic church, in something of a return to the spirit of Caravaggio’s Counter Reformation imagery, began to realize that promoting the mystical connection between Christ and the lower classes was becoming a necessity. In his 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum (On the Condition of the Working Classes), Pope Leo XIII argued for the maintenance of the traditional social order and against the socialist breakdown of class structure, reminding the lower classes that poverty was the chosen lot of Christ.

This connection is depicted in Lhermitte’s 1897 pastel of Christ transported to the French countryside, The Samaritan at the Well (La Samaritaine) (fig. 5). It was inspired by Sarah Bernhardt’s title role in La Samaritaine, which she successfully opened at her theater in Paris, the Théâtre de la Renaissance, during Holy Week, 1897 (fig. 6). 1897 was also the centenary of the permanent display of the Mona Lisa at the Louvre. Then as now, it is a pleasure to welcome her back on the job!

* Niccolò Lorini del Monte, Elogii delle più principali S. Donne del sagro calendario (Florence, 1617), p. 316, translation quoted in Pamela M. Jones, Altarpieces and Their Viewers in the Churches of Rome from Caravaggio to Guido Reni (London: Routledge, 2016), p. 75.

Illustrations

Fig. 1. Alone at last. At the Louvre Museum, Paris. (after Leonardo da Vinci (Italian, 1452–1519), Mona Lisa (Portrait of Lisa Gherardini), oil on wood panel, ca. 1503–19, Musée du Louvre, acquired by François I in 1518, Inv. 779).

Fig. 2. Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (Italian, 1571–1610), Madonna of Loreto, ca. 1605–06, oil on canvas, Cavalletti Chapel, Church of S. Agostino, Rome. Wikimedia / Public Domain.

Fig. 3. William-Adolphe Bouguereau (French, 1825–1905), The Water Girl, or Young Girl Going to the Spring, 1885, oil on canvas, Dahesh Museum of Art, 1995.1.

Fig. 4. Léon Augustin Lhermitte (French, 1844–1925), Picking Lilies of the Valley, 1887, charcoal on laid paper, Dahesh Museum of Art, 1996.11.

Fig. 5. Léon Augustin Lhermitte (French, 1844–1925), The Samaritan at the Well (La Samaritaine), 1897, pastel on paper, adhered to canvas, Dahesh Museum of Art, 1997.52.

Fig. 6. (Phot. Bert)., La Samaritaine (premier acte). La Samaritaine, Sarah Bernhardt. Jésus, M. Brémont. Illustration for L[éon] Brémont, “Musique: Festival Pierné, Conférence de M. L. Brémont,” Journal de l’Université des Annales, 5e année (année scolaire, 1910–1911), 1, no. 4, (1 Février 1911): 231, Dahesh Museum of Art.