Images of the famous appear today primarily in printed and social media. But 19th-century France revived an Italian Renaissance invention and recorded celebrity likenesses on portrait medals as well as in the traditional modes of painting, prints, drawings, and sculpture. These small metal objects—varying in shape and size—were cast (by pouring molten metal into a mold) or struck (by pressing the image on a blank disk held between two dies). Typically, the front (obverse) features a portrait, and the back (reverse) a symbol, emblem, or allegory of the sitter’s qualities, accomplishments, or biography. The Dahesh Museum of Art holds a rich collection of representations of famous artists working in France during the 19th century.

Pierre-Jean David d’Angers (1788–1856), an influential and important sculptor, was a key figure in the revival of portrait medals in the first half of the 19th century. Besides his public monuments (including the famous pediment of the Panthéon in Paris (1830–37), David produced busts and over 500 medallic portraits of his renowned contemporaries. His 1832 portrait medallion (basically, a large medal) of the painter Paul Delaroche (1797–1856) presents the sitter in profile in the tradition of ancient Roman coins, a viewpoint that David considered to be most expressive and comprehensive.

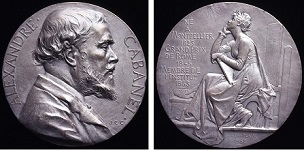

Jules-Clément Chaplain (1839-1909) followed David, becoming a premiere medalist in the second half of the 19th century. A winner of the Prix de Rome for medal engraving in 1863, Chaplain then had a highly successful career and in 1877 was named the official medalist of the French government. Besides presidential portrait medals, Chaplain created many animated and realistic portraits of his fellow artists and was one of the first artists to use both cast and struck technique, taking advantage of the development of the reducing machine in the 1830s—which enabled sculptors to make a large-scale medal design and then reduce it mechanically. Chaplain’s reverse designs are considered among the most important in the history of the medal. His 1888 portrait of Alexandre Cabanal (1823–89) shows the painter in profile, while the reverse features a female allegory of painting with an easel, palette, and brushes. The reverse of his 1866 silvered bronze medallion of the sculptor Eugène Guillaume (1839–1909) reveals a female allegory of sculpture holding a hammer and chisel, seated before a large sculpture. His 1885 portrait of painter/sculptor Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904) is very specific to the subject’s favored interests, a female personification of painting surrounded by Cairo’s Sphinx, Istanbul’s Blue Mosque, and a Roman gladiator’s helmet.

A maker of painted wax sculptures, ceramics, and bronze statues, the Alsatian Jean-Désiré Ringel (1847–1916), known as Ringel d’Illzach, also produced many portrait medals of celebrities of the day. The portrait of Léon-Augustin Lhermitte (1884) is an excellent example of Ringel’s attention to the interaction of the portrait with the surrounding field. He incorporates the painter’s name, palette, and profile with proto-Art Nouveau elements, such as serif lettering and the repeated curved lines of the palette’s edge and finger holes.

The art of the medal continued to flourish in late 19th- and early 20th-century France. In 1899, the collector and art critic, Roger Marx created the Société des amis de la médaille française (Society of Friends of the French medal). In the 1890s, the Musée du Luxembourg (now the Musée d’Orsay) began its own collection of medals. As new ideas in art and taste swept Europe, however, medallic art lost its appeal. What remained was an exceptionally rich collection of celebrity portraits of a bygone era.