Greek and Roman myths have told stories of life, love, death, courage, good, evil, and innocence and inspired the popular imagination for centuries. Mythology, together with stories from Classical history and the Bible, was the primary source for the 19th-century history painter and sculptor. The French Academy considered history as the highest-ranking category in art, because it represented the cornerstones of the academic tradition — the human figure, passions, and intellect — and provided an endless source of subjects and themes. Some artists chose motifs relating the heroic actions of mankind. Prime examples of such works are paintings by the Neoclassical painter and collector, François-Xavier Fabre (1766–1837), and the bronzes of the Romantic sculptor, Antoine-Louis Barye (1795–1875). Fabre’s Oedipus and the Sphinx (ca. 1806–10) illustrates Oedipus, the legendary figure from Greek mythology, confronting the deadly riddling Sphinx: “What is that which at dawn walks on four legs, at midday on two, and in the evening on three?” Those who failed to answer correctly were killed, indicated by the skulls surrounding the Sphinx. Oedipus triumphantly answered that it was man, who crawls as an infant, stands on two feet in maturity, and uses a stick in his old age. Barye, on the other hand, opted for an actively charged episode from Ovid’s Metamorphoses describing how Theseus, ruler of Athens, helped the king of the Lapiths by violently slaying the part-human part-horse centaur Bianor.

Alternatively, stories of love could delight the senses and often embody a moral meaning. Henry-Pierre Picou (1824–95), who championed the revival of antiquity, focused on one of the most popular Greek myths, the Judgment of Paris, the episode that instigated the Trojan War: Paris had to choose the fairest of the three goddesses— Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite (identified by the Romans as Juno, Minerva, and Venus). He chose Aphrodite, seen here receiving the golden apple, who then helped the Trojan prince win the beautiful Helen and carry her off to Troy.

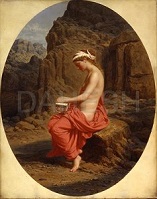

Other artists tackled stories of human misfortune and hope, notably represented by Pandora, who was the first woman created by the Greek god Zeus (known as Jupiter by the Romans) and sent to earth. According to legend, when Pandora opened the jar she carried, the disasters within escaped and the idyllic Golden Age ended. Only Hope remained as a consolation for mortals. In Pandora’s Box (ca. 1877), Paul Gariot (1811–80) sets Pandora in an eerily barren, almost apocalyptic landscape, evoking the inevitable fate that looms over the human race.

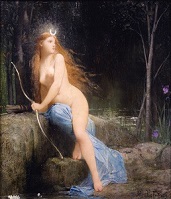

Classical mythology also provided artists with the opportunity to portray sensual female nudes, an increasingly popular subject matter among private collectors in the mid-19th century. The two Roman goddesses, Diana (known as Artemis in ancient Greece) and Venus were among the celebrated stars at the Paris Salons. Jules-Joseph Lefebvre (1836–1911) rendered the seductively nude Diana, goddess of the hunt, in porcelain tones, her body highlighted against the blue fabric and a dark background. The example par excellence is Alexandre Cabanal’s (1823–89) famous painting, The Birth of Venus, which he exhibited at the Salon in 1863 before its purchase by Emperor Napoleon III (Musée d’Orsay, Paris). According to the Classical myth, Venus, the goddess of love and beauty, was born of sea-foam and floated ashore on a scallop shell. The artist here omits the shell, portraying Venus languidly reclining on the crest of a wave. The Dahesh version is the most famous of the two known signed and reduced-size replicas, frequently mentioned and reproduced in 19th-century books and journals.

Despite the increasing popularity of scenes of daily life, Classical mythology continued to inspire some avant-garde artists, including the Symbolist painters Gustave Moreau (1826–98) with Oedipus and the Sphinx (1864, Metropolitan Museum of Art) and Odilon Redon (1840–1916) with Pandora (ca. 1914, Metropolitan Museum of Art).